Today has to be perfect.

Magic.

I look at the clock.

10:14 AM.Ten fourteen. One plus one is two plus four is six plus ten is sixteen minus one is fifteen minus two is thirteen. OK.

I turn from the clock and walk into the hallway. “Ready.”

Saturday will be the third state soccer championship in a row for Jake Martin. Three. A good number. Prime. With Jake on the field, Carson City High can’t lose because Jake has the magic: a self-created protection generated by his obsession with prime numbers. It’s the magic that has every top soccer university recruiting Jake, the magic that keeps his family safe, and the magic that suppresses his anxiety attacks. But the magic is Jake’s prison, because sustaining it means his compulsions take over nearly every aspect of his life.

Jake’s convinced the magic will be permanent after Saturday, the perfect day, when every prime has converged. Once the game is over, he won’t have to rely on his sister to concoct excuses for his odd rituals. His dad will stop treating him like he is some freak. Maybe he’ll even make a friend other than Luc.

But what if the magic doesn’t stay?

What if the numbers never leave?

Acclaimed author Heidi Ayarbe has created an honest and riveting portrait of a teen struggling with obsessive compulsive disorder in this breathtaking and courageous novel.

Category: mental illness

Finding light in the darkness

I’m going to write about two things that personally motivated me to deal with my own demons in a very public way. The short-term inspiration for this is me rereading the acknowledgements section of Redemption. The longer-term inspiration for this is a public tragedy and a low period in my life.

Okay, first, here’s a small section of the acknowledgements in Redemption:

To Robin Williams. Yours was a life well lived, and I hope to be part of a positive story of those influenced by how it ended.

Let me go backwards. Robin Williams completed suicide on August 11, 2014. He had long suffered from a slew of mental health challenges, including depression and substance abuse. However, Williams was suffering from “diffuse Lewy body dementia,” which ultimately contributed heavily to his suicide.

William’s suicide ultimately inspired me to go public with my story. That started when some idiot on Facebook decided to spout off shortly after Williams’ death by saying something along the lines of, “So sad Robin Williams committed suicide. He just needed to pray to Jesus more!”

No, you schmuck, that’s not how it works, and that ignorant comment got me so damn fired up that I wrote an op-ed in my local paper, detailing my own struggles with depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation. That, in turn, set my career in motion in a very different way, making me become much louder about mental health issues. I’ve spoken at events detailing my own struggles, cofounded a mental health caucus, appeared in PSAs and introduced legislation designed to help those who are suffering from mental health challenges. I know that the work I’ve done in this realm has helped people – and I know I have a lot more to do to help more.

It also inspired this speech, the most difficult one I have ever made:

Fast forward about seven or eight months, and I’m struggling, in the midst of one of the most depressed periods of my life. I’m struggling at work, my wife is struggling at work, and life just generally sucks at the moment. I go back to see my therapist. I increase my medication. And then I realize something else: I desperately need an outlet. Something to help get me through everything I am suffering from. I decide to start writing again – I wrote fiction as a kid and had published the non-fiction book I wrote, Tweets and Consequences.

And I remember this goofy plot idea I had as a kid, twenty years ago, about kids getting trapped on a spaceship. And I realize something: That’s not a bad plot. But what if I could make it more? What if I could fold in a mental health message as well?

And thus, Redemption is born.

For what it’s worth: I have a character named Robin in Redemption. In all fairness though, that’s also my daughter’s middle name, so let’s call that character’s naming a 50% tribute to Williams and 50% tribute to my daughter.

The death of Robin Williams helped me and countless others find their voice and seek help. I know that this may be cold comfort to those he loved and those who loved him. But I sincerely hope that they can take some solace in knowing that Williams’ life and death helped so many, including me. His was a life well lived – and, as I said above, I hope to be a small part of that story.

You can always find light in the darkness. Pain makes us great, and with time and therapy, you can turn the most agonizing periods of your own life into something incredible.

As long as you breathe, there is hope. The trick is just finding it sometimes.

Six questions: An interview with Mia Siegert, author of Jerkbait

Even though they’re identical, Tristan isn’t close to his twin Robbie at all—until Robbie tries to kill himself. Forced to share a room to prevent Robbie from hurting himself, the brothers begin to feel the weight of each other’s lives on the ice, and off. Tristan starts seeing his twin not as a hockey star whose shadow Tristan can’t escape, but a struggling gay teen terrified about coming out in the professional sports world. Robbie’s future in the NHL is plagued by anxiety and the mounting pressure from their dad, coach, and scouts, while Tristan desperately fights to create his own future, not as a hockey player but a musical theatre performer. As their season progresses and friends turn out to be enemies, Robbie finds solace in an online stranger known only as “Jimmy2416.” Between keeping Robbie’s secret and saving him from taking his life, Tristan is given the final call: sacrifice his dream for a brother he barely knows, or pursue his own path. How far is Robbie willing to go—and more importantly, how far is Tristan willing to go to help him?

About the same sort of feedback I’d give for Robbie, honestly. Mental illness is something that affects many people. It doesn’t discriminate. Counselors will focus on different things for each person’s needs.

Depression is massively, frighteningly increasing

Some frightening news last week, according to health insurance data from Blue Cross Blue Shield:

-

Major depression has a diagnosis rate of 4.4 percent in the United States, affecting more than 9 million commercially insured Americans.

-

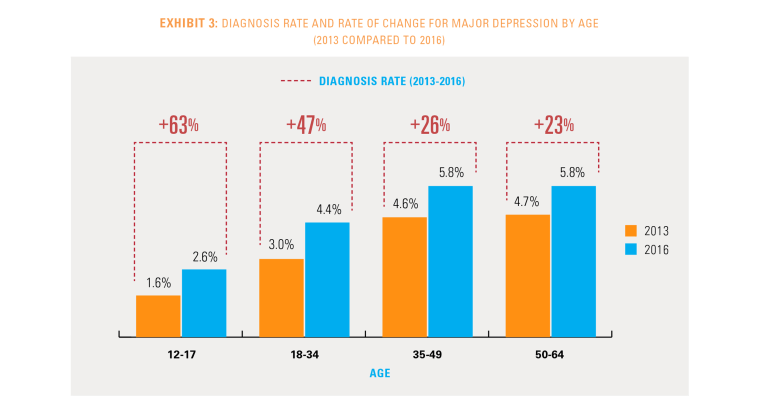

Diagnoses of major depression have risen dramatically by 33 percent since 2013. This rate is rising even faster among millennials (up 47 percent) and adolescents (up 47 percent for boys and 65 percent for girls).

-

Women are diagnosed with major depression at higher rates than men (6 percent and nearly 3 percent, respectively).

The report also found that younger generations are seeing the largest increase ind depression rates:

By the way, keep in mind that this data is from among those who have health insurance – and we know that there are millions of Americans who do not, and those in poverty are more likely to be depressed…so this is an underestimation.

This is a genuinely terrifying. We should all be deeply, deeply worried about the findings of this report, findings that, unfortunately, ring true.

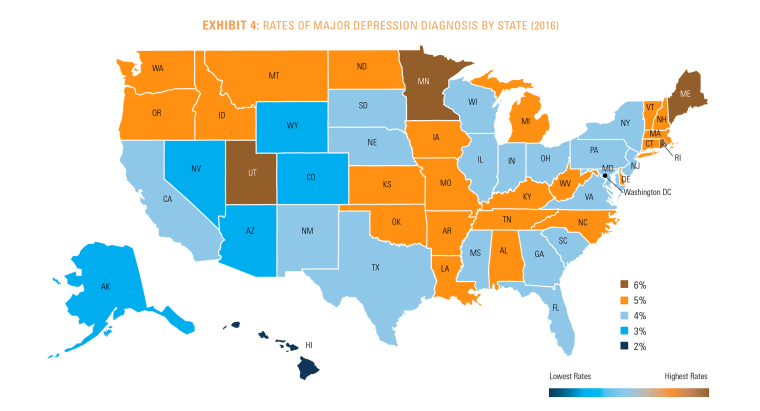

Also worth noting: Rates of major depression vary significantly on a state by state basis:

The NBC article on the subject referred to a variety of potential causes for the increase, including:

- An increasing sense of business in our day to day lives and a loss of community that comes with it.

- Overall world events and our increasing awareness of the trauma that exists…everywhere.

- Social media.

- Overdependance on smart phones.

We’re going to have to start treating depression for what it is: A major public health crisis. I won’t pretend to be fully capable of developing every solution – and certainly not solutions which are politically viable (treating mental health for everyone requires infusing billions of dollars into the mental health system, and we’re not doing that anytime soon, sadly). And I’ll add this: Many of the items which would really reduce depression are societal and cultural changes that are largely beyond the reach of government. They include things like slowing own our daily lives, increasing family and community bonds, and taking our phones and throwing them out the window.

But the fact is this: We have to do better. As I write this entry I am staring at my children and I worry, given this world and their genetic predisposition, that this will be them one day. Families have to now constantly be on the lookout for potential mental health problems. They have to teach coping skills and resilience, and they have to be willing to seek treatment when symptoms of mental illness/depression begin to display themselves. I wish I’d realized this when I was younger – early treatment for mental illness – like for most illnesses – is critical.

My mission with this blog is largely to discuss mental health and raise awareness. It’s becoming apparent that this awareness is more needed now than ever.

The most common age group to complete suicide is not what you’d think

For obvious reasons, you cannot discuss mental health without discussing the tragedy that is suicide. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, we lose nearly 45,000 Americans a year to suicide, making it the 10th leading cause of death in this country.

My experience when it comes to suicide and age is this: Most folks, generally speaking, think that suicide is something that primarily strikes younger kids, particularly those in high school. I think there’s a few reasons for this. First is suicides portrayal in popular media, such as the Netflix show 13 Reasons Why. This is just a personal hypothesis, but I think that those who are younger have broader communication skills – as a result, when a young person attempts or completes suicide, you are more likely to hear about it.

Interestingly, this assumption is not born out by the data. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, here is a breakdown of suicide completions by age:

As you can see, the most likely group to complete suicide is not teens or young adults; it’s actually those aged 45-54, followed by individuals who are 85 or older.

What is very frightening, however, are the overall trend lines. For far too many of these age groups, suicide completions are on the rise, and have been for some time. But no where is this trend more pronounced than among those who are between 15-24, which have seen a nearly 20% spike since 2012, a rate of increase far outpacing those in other demographic groups.

There are many potential reasons for this, including rising rates of depression and anxiety among teens in general, the use of smartphones ad cyberbullying that comes with social media.

Regardless of the reason, the trend line is obviously incredibly disturbing, but it remains vitally important that we deal with suicide for the public health crisis it is among all age groups.

Talk to the kids: Why you should tell your mental health story

This past Friday, as part of the real job, I had the pleasure of attending career day at one of my local elementary schools. During that time, I spoke with about 70 5th graders about what it’s like to be a State Representative, what I do, what my issues are, etc. In doing so, did what I always did: I spoke about mental health. I also made sure to be very clear – no euphemisms, and no sugar-coating. I spoke about having depression and anxiety disorders – what that means – and how I see a therapist as needed and take medication on a daily basis.

I make this part of an overall anti-stigma conversation. If I’m talking to younger kids, I broach the subject like this:

“Okay, let’s say you’re riding you’re bike, and you fall off and your arm is hanging at a funny angle.” (imagine me holding my arm at a funny angle) “What’s the first thing you are going to do?”

“Cry!”

“Yes, well, there’s that, but AFTER that.”

“Call 911!”

“Right! Exactly! You’ll call 911! And you would’t even think about it, right? You wouldn’t be embarrassed. Well, imagine having a mental illness….”

And I take it from there.

Sometimes, the kids ask me questions about this stuff. Other times, they delve into other areas of my career. In two of the three classes I had, the mental illness did come up. I was asked questions about it, and they were strikingly perceptive. Two that stick out in my mind:

- Is suicide a mental illness?

- Is it a mental illness if you do drugs?

And then a few kids opened up and discussed their own experiences – or that of their family – with mental illness. I know no one would be able to identify them from this, but I’d still rather not say what they said. Suffice to say – it struck me. It left a mark. And it reminded me of one of the many reasons I always discuss my mental illness, but particularly with kids: It can give them a little bit of hope. As many of you unquestionably know, one of mental illness’ greatest challenges is the way it warps your mind, makes you feel like you are alone. I want all of these kids to know that they aren’t alone.

This leads me back to my main point: Tell your story. Please understand I say this not to toot my own horn, but the smartest decision I have ever made in my life was to publicly discuss my own struggles with depression and anxiety. The experience has become astonishingly positive, and has helped me help other people. According to research, a contact-oriented strategy, one in which regular people share their own struggles with mental illness, can be invaluable towards fighting the stigma that keeps people locked in shame and out of treatment. Telling your story can provide incalculable hope to others who need it.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts and perspective. Have you “gone public” with your struggles? What has your experience been like?

Put down the damn phone

The above picture was taken the other day. My wife and I were lucky enough to go see Haim (my favorite group!) at Radio City Music Hall. I’ve been reading this fascinating book lately: How To Break Up With Your Phone, by Catherine Price. It is, as the name says, all about learning to live your life with less reliance and obsession with your phone. To be clear, it isn’t about stopping phone use, but being more conscious of it’s use.

At one point, the book offered this: Take a look around, wherever you are. How many people are on their phones? I’d never really done it, so I thought, sure. I looked and saw this picture. All those little lights? Phones. And the picture doesn’t do it justice – there were plenty more. Granted, this was a relatively young audience and it was before the concern started, but I was still floored. Most of the folks on their phones seemed to be sitting with other people. Were we all really ignoring our friends and loved ones to stare at a shiny box?

I’ve written about it before, but it seems worth saying again: Put down your phone, if you can and if you don’t need to have it in your hand. I have to admit that I can’t believe I’m typing this, because I am notoriously bad with phone use, but it is something I am trying to change because I have to.

Why should you try to use your phone less? Well….

- It can make you sleep less, and hurt your sleep quality.

- They encourage and make multitasking easier, and that damages productivity.

- They have been linked to an array of societal problems, including depression and suicide.

- They hurt our ability to form relationships with others and participate in society as a whole.

Price makes a couple of arguments that never quite occurred to me before as well: Every second with our phones is a moment robbed from doing something else, be it reading a book, taking in nature, hanging with family and friends, whatever. We take our phones out when we are bored, but it is in the moments that we pause for silent reflection that our brains have time to catch up with the world, to process and to develop new ways of thinking and insight into current problems.

Just to be clear, I don’t want to put my phone completely down, and I don’t plan on doing so. A better way to addressing when to pick your phone up and when to put it down, as far as I am concerned, is to make sure you know why you are using your phone. Are you doing it because you are bored? Do you want to get lost in the “scroll hole”? If so, maybe reconsider your use. But is there a conscious reason you want to use your phone? Looking for a fact that came up naturally in the course of a conversation with your friend? Want to show them that hilarious video? Those uses make sense to me, as they are part of an overall social interaction.

Again, I highly recommend How To Break Up With Your Phone. It’s been helpful to me already. It also encourages you to download an app to track your use, and I already did that, going with Moment.

Any thoughts you want to add to this? I’d love to hear them because I want to know if this prospective is one that’s shared. What do you think? Let us know in the comments below!

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation?

You know, you first hear about something like this, and you think it sounds like some sort of witchcraft nonsense. Magnets? To help depression?

Apparently. And it’s scientific based.

I write about this now because I had an appointment last week to explore this as a treatment possibility, and it is likely something I’m going to pursue. Here are the basics, per the Mayo Clinic:

During a TMS session, an electromagnetic coil is placed against your scalp near your forehead. The electromagnet painlessly delivers a magnetic pulse that stimulates nerve cells in the region of your brain involved in mood control and depression. And it may activate regions of the brain that have decreased activity in people with depression.

Though the biology of why rTMS works isn’t completely understood, the stimulation appears to affect how this part of the brain is working, which in turn seems to ease depression symptoms and improve mood.

The most important question, of course, is this: Does it work? According to the evidence I have seen, yes, and that’s in tests involving a placebo. More research is needed, but this appears to work.

Thankfully, the side effects are very mild, per the Mayo clinic.

Side effects are generally mild to moderate and improve shortly after an individual session and decrease over time with additional sessions. They may include:

-

Headache

-

Scalp discomfort at the site of stimulation

-

Tingling, spasms or twitching of facial muscles

-

Light headedness

The biggest drawback, as best I can tell? The Doctor I spoke with told me its most effective to do it every single day, for 4-6 weeks. Session, I think, are 30-45 minutes. That’s a heck of a time commitment. That being said, sucks for me. It’s not the Doctor’s fault that this is the way the brain works, but it’s certainly a challenge with my schedule – going to Harrisburg and vacation means I won’t have that kind of time until August.

So, let me conclude by asking you for your experiences. Have any of you out there had TMS? Any experiences to share? I’d love to hear them!

Why “Redemption”

As I said in an entry the other day, I have a book coming out on June 5. It’s called Redemption, and it’s about depression, anxiety and saving the world. From the blurb:

Twenty young people wake aboard the spaceship Redemption with no memory how they got there.

Asher Maddox went to sleep a college dropout with clinical depression and anxiety. He wakes one hundred sixty years in the future to assume the role as captain aboard a spaceship he knows nothing about, with a crew as in the dark as he is.

Yanked from their everyday lives, the crew learns that Earth has been ravaged by the Spades virus – a deadly disease planted by aliens. They are tasked with obtaining the vaccine that will save humanity, while forced to hide from an unidentified, but highly advanced enemy.

Half a galaxy away from Earth, the crew sets out to complete the quest against impossible odds. As the enemy draws closer, they learn to run the ship despite their own flaws and rivalries. But they have another enemy . . . time. And it’s running out.

Now, here’s the question I keep getting: Why is it called Redemption?

First is the obvious: It’s the name of the ship. But it’s the name of the ship in the book for a reason.

Okay. So I wrote this thing not just to tell a science fiction story, but to tell a story of mental illness and give those who suffer hope. That’s sort of been my driving force, as an elected official and advocate for the mentally ill. And to be perfectly honest, that permeates just about every facet of the book. Including the name of the ship.

I named it Redemption because I think the idea of guilt – and seeking Redemption – was and is a big part of my depression. Guilt is a common symptom of depression. It’s something I certainly got to know in a very personal way. And I spent most of my life searching for redemption. I desperately wanted to be redeemed from some unknown sin. And I think that’s something that’s relatively common among those who have suffered.

The entire plot is, at it’s core, a redemption story, but not from a sin: From mental illness, from depression and from anxiety. It’s a redemption that I think we all strive for. In my experience, it’s almost not complete obtainable. Personally, I know I will never be completely free from mental illness. It will always be there, running in the background like an iPhone app. Recovery isn’t an end state, it’s a journey. And that’s a lesson I that I have tried to learn all my life, and a journey I try to highlight in Redemption.

As always, I’d love to have your thoughts. Is this an experience you understand? No? Either way, let us know in the comments!

“So, what are you going to do about it?”

One of the most impactful memories of my life occurred somewhere in the late summer of 2012. At the time I was +220 pounds, and I’m about six feet tall, so this was way up on where I should have been. I had just eaten a ton and had the misfortune of standing on the scale, thus depressing myself more than usual.

Anyway, I was in my living room with my wife, sitting on the couch. My wife had completed her own significant weight loss journey a few years prior, dropping fifty pounds, so I knew she would understand my sadness over my weight and where I was.

So, there I sat, complaining to my wife about my weight. She was silent, nodding, as I listed how upset I felt at what I had allowed myself to do to my body. And then, finally, she asked me this question:

“So, what are you going to do about it?”

That was the question that changed my life. I mean, there I was, complaining about how miserable I was, and I hadn’t done a damn thing to make it better. That wasn’t fair and it wasn’t right. How dare I complain when I hadn’t even tried to improve? So, right then and there, I decided to do something.

In terms of weight loss, I got lucky in that my body was more amenable to losing weight than that of many others. I downloaded a calorie tracker from Livestrong and used that, and exercise, to shift my mindset. Staying in my allocated calories became like a game. And, over time, it worked. I dropped thirty pounds and kept them off. I’m in better shape now than I was in my 20s.

Now, that being said, in writing my blog entry earlier this week, I remembered this question and how it applies to mental health as well. That entry dealt mainly with what I wish every “support person” knew about depression and mental illness, and one of the items mentioned was that none of us really want to be depressed, and we’d all love to get better.

Allow me to propose this question then, support people. It’s the question that you may want to ask when the depressed/anxious person that you love is in pain. You may want to ask it in the most non-judgmental, softest way possible. You also may want to ask it in a tough love sort of style, as my wife did to me:

“So, what are you going to do about it?”

Depression sucks. It does. And it’s taken me years and years to realize that it’s not a weakness and not my fault. Indeed, it’s not the fault of anyone who has it. But there is a big difference between not my fault and not my responsibility. All of us who suffer from some sort of mental illness have an obligation to do something about it. That may mean doing little things on our own time, like exercise or meditation. It may mean seeing a therapist or psychiatrist to discuss medication. But above all else, it means managing our disease.

Support people, here’s where you can come in. Ask us this question. If the depressed person you love truly wants to get better, they’ll need an answer. They’ll need to do something about it in order to get better or get through the rough patch they are in. It is a question I have to ask myself from time to time when things get bad. Sometimes the answer may be, “Wait a week and see if I’m this miserable still – if I am, I’m going to see my therapist.” Sometimes the answer may be, “I’m making a call now!” But above all else, there needs to be a real answer.

And, as always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! How do you ask your loved one or yourself this question. What has your experience with this been like? Let us know in the comments below!